“If you’re the first to do something, you’re allowed to fail. If you just come along with the mainstream you can’t fail.”

Here’s the next installment of the Public Libraries 2020 articles I wrote for the Reading and Writing Foundation and it’s a pretty mind blowing one.

Aarhus libraries and their director Rolf Hapel are rightly well known in the library community. They are hosting the Next Library conference this September in their impressive new waterfront library building. But, as this article shows, they’ve been showing us how it’s done (and thinking about how to do it in future) for many years…

All quotations are from Rolf Hapel. All images supplied by Aarhus libraries unless otherwise credited.

Context

Aarhus is the second largest city in Denmark. The economy of the city, along with the rest of Denmark, has been transforming from an industrial base to a knowledge-based economy. There has been a particular move towards urbanisation of the population, with rural areas moving from a primarily small scale agricultural economy to a large scale farming and leisure-based economy.

Another challenge for the country is the ageing population in Denmark, although the city of Aarhus remains quite young because a number of educational institutions are based there. The economy is currently relatively stable and although the financial crisis had an impact in 2008 there are signs of growth.

As many other European nations Denmark has a problem with illiteracy – around 15-20% of the population have a reading age of 8 years (2nd year of primary school). In addition, the population needs to develop its computer and media literacy as many social services are moving to an online-only presence which relies on citizens to ‘self serve’ using web based services. Although there is a high penetration of fast broadband and mobile web-enabled devices such as smart phones and tablets, around 30% of the population are not able or confident to use public services online and also do not understand why they should do so.

Libraries are included in the government digital strategy as places to get help in using public services and increasingly they are the only physical presence of government services on the high street as housing and benefits offices are closing their doors.

“Increasingly, physical libraries are about physical people. Where we used to be book oriented we are now human oriented”

There are 18 libraries in Aarhus, and the new central library DOKK1 opened in June 2015.

The process of change

“The process of change has been longer than you might imagine. We have been talking about the paperless office since the 1980s. We had the first e-readers in the late 1990s. Libraries in Denmark have been at the cutting edge of finding new ways of distributing knowledge.”

Because of this, Danish policy makers see libraries as a tool to educate the Danish population, particularly about how to engage with digital public services. Libraries are neutral spaces that are free to enter and don’t require you to have a specific religious or political affiliation.

The new library building

(Image courtesy of Freek Zonderland)

The local public were involved in designing the building and workshops were held with school children to get them to provide a brief to the architects about how they wanted the building to be designed.

“We thought that today’s children are tomorrow’s adult library users, and we want this building to work for them throughout their lives, so why not involve them in the planning of the building? The architects were sceptical at first but when they saw their ideas – particularly in relation to soundscapes, they were really inspired.”

Dukketeater for børn på Åby Bibliotek, Åbyhøj

© Foto: Søren Holm/Chili

Dato: 05.09.03

Chili foto & arkiv

Fostering innovation

In Aarhus the municipal government had a decentralisation scheme implemented in the late 1990’s. Institutions were given budgets and allowed to spend them as they saw fit within certain boundaries. This liberated the library and allowed it to become more innovative in its approach. The library invested more in technology and less in staff posts that were no longer needed – it became leaner and more efficient. Plans and ideas were also easier to realise.

The library began an innovation policy which saw staff members being invited to propose new services every year. These proposals are assessed and the best ones are invited to pitch their idea in person to the library management team. If they are successful the staff member is allowed a certain number of days to work on the project where they are relieved of their other duties. They are also promised a certain amount of matched funding from the library service if they are able to source funding from other partners, and they are given support to do so. In this way the library has managed to raise at least €1 million annually from external funding to develop services in connection with partners.

One example of a project that began in this way is the “Digital ABC” curriculum which the library staff developed together with local secondary school teachers. The aim of the curriculum is to teach young people how to access important digital public services. Having started in Aarhus it is now being taught across Denmark.

New delivery models

“We are working out how to run the libraries with a minimum of effort, through co-creating services with our communities”

There were 2,044,089 physical visits in the 18 libraries in Aarhus in 2014. Of those were 409,133 visits took place in the periods where there are no staff (the so called “open library”).

“One way of thinking about it is to call it the ‘mashup’ library. We provide a space and then import services that have been developed and delivered by others into that space. Just like you might mash up a weather report or traffic information into your website”

Sundhedsuge på Gellerup Bibliotek, udstilling og vejledning om sund og usund kost for bl.a. indvandrere, her pige med tørklæde ser på sukkerindhold i forskellige drikke.

© Foto: Søren Holm/Chili

Dato: 09.10.03

Chili foto & arkiv

One example of where this has worked particularly well is in areas with high immigrant populations where the library has partnered with health services so that midwives can offer information to pregnant women. Midwives then continue to work with children’s librarians to help young families run events and family reading groups so that they get the support and information they might not otherwise find.

“Libraries are mediators, the content they mediate can change. I’m not worried that this approach will dilute the library brand – we know what we are.”

Leveraging friends groups

“A lot of friends groups were started in Denmark in the early 2000’s when libraries were under threat. Although they can often be seen as a conservative force, in Denmark they are actually very progressive and they support libraries to try new things.”

Friends groups have been instrumental in funding expensive author visits to libraries and approaching authors to ask them to come to the library and speak to library users.

Innovation as a service

Aarhus libraries are working with Chicago Public Libraries and IDEO (an innovation business) to develop a toolkit for libraries to undertake rapid innovation and teach staff to think in terms of design. Specifically, they are looking at bringing in service users to co-create services.

Lifelong learning

Trige Kombi-bibliotek, kombineret skole- og folkebibliotek, her børn fra Bakkegårdsskolen og almindelig bruger.

© Foto: Søren Holm/Chili

Dato: 09.10.03

Chili foto & arkiv

Approaches to learning in libraries have changed over the past 20 years:

“It’s not just about the physical entity of the book providing learning opportunities. It’s about human development, social cohesion, knowledge and idea spreading”

Lifelong learning in libraries is not just about the library’s collection of books, although that is still important. Libraries have always been about mediated learning and now they are also mediating the knowledge and learning that is held in the community. There is a change of focus from the book collection to the humans that engage with the library.

“Books are not the only source of knowledge transfer we have in the library – we also have knowledge in our communities and libraries can be places where ideas are spread.”

Mor læser bog for sit barn, læsetrappen på Børnebiblioteket på Hovedbiblioteket i Århus.

© Foto: Claus Haagensen/Chili

Dato: 27.09.03

Chili foto & arkiv

Lifelong learning activities and services in libraries are co-developed with library users. In 2014 Aarhus Public Libraries had 1651 events. One example is the knitting club in Aarhus started because some women used to meet at the library to knit. The library staff asked them if they would be happy to include others in their knitting group and then proposed speakers and experts to come and talk to them about knitting. Club members were given advice and information about resources the library holds on knitting and asked to make their own book recommendations and the service grew from there.

“When people come through the door of the library we don’t see them as clients, we see them as resources. They all know something and can do something”

Partnership is also a key element of delivering lifelong learning support. For example, homework help cafes are delivered by the Danish Red Cross Youth Division four times a week in three libraries across Aarhus.

Reading groups are another strong trend in Denmark that are being supported by the library service. The library service has set up a website www.litteratursiden.dk which puts Danish readers in touch with each other, helping them to find out about reading groups taking place in libraries and other places nearby. It also connects readers with authors: the site lists all contemporary Danish authors and their works and allows readers to contact authors with questions and comments. The site also facilitates contacts between reading groups and libraries, so that they can borrow books from the library and use other library services. Although it is a user-driven service, the service is facilitated by the library service. This service also demonstrates the interconnections between the digital and physical world and new ways in which they are influencing each other. In 2014 the site had 3,313,091 unique visits with 11851 people have established profiles on the site. But the impact is also felt in Aarhus libraries- there are 211 readers clubs registered in Aarhus libraries, with between 8 and 15 members in each. Registering with the library means that each club has a borrowers card that allows for special lending rights, such as several issues of the same title, and support in acquiring books from other libraries if needed.

Theories of the library

In my interview with him, Rolf Hapel described a “four room model” for what a library is that I thought it would be useful to share – although not all of these will be contained within the physical building, or be discrete from each other in practice:

- The inspiration space

A space for serendipitous learning – where you can find out about things you didn’t even think you were interested in

- Learning room

A place where you can access structured knowledge – either through book, e-resources or classes, peer-to-peer learning without having to be a member of an educational institution

- Meeting space

A space for democratic dialogue, where you can hold workshops, exchange views and ideas and where the community can ‘borrow’ physical space to do activities that are free to access and fit with the library’s public purpose

- Performative space

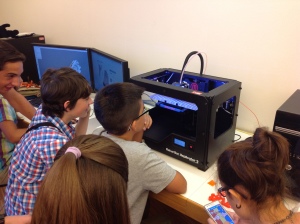

These are maker spaces, hack spaces and other ways of expressing yourself – poetry slam workshops and other creative activities that can take place in the library

Since the 1600s Pistoia has had an impressive library housed in the historical centre of the town. The building is a beautiful example of Renaissance architecture. It also houses an important collection of historical manuscripts and books. However, the library was never well used by the local population. It had a circulation of around 23,000 loans per year and was mainly used by students and visiting scholars.

Since the 1600s Pistoia has had an impressive library housed in the historical centre of the town. The building is a beautiful example of Renaissance architecture. It also houses an important collection of historical manuscripts and books. However, the library was never well used by the local population. It had a circulation of around 23,000 loans per year and was mainly used by students and visiting scholars.